As a lapsed entomologist I barely keep one foot in the door of insect science. I get text messages of bugs sent to me by friends, “What is this? Should I be worried? How do I get rid of these? Look at this interesting critter!” Clearly I am their bug guy. Before modern cell phones I might get them taped to an index card, in a vial of alcohol or dried in a small gift box. When I was an entomologist I considered myself a medical/veterinary entomologist and parasitologist, so unless it was a blood sucker or intestinal worm, random bug pictures sent me scrambling for general entomology information. While “Google is your friend”, I also rely on my beetle guy, my moth guy, my aquatic ent(omology) guy, and so on. In the conservation biology world I have my fish guys, my bird and butterfly gal, my native plants gal, and even a snail guy. Jake Francis is my bee guy. It might be an over simplifying title, Jake (@pollinationecology) is a pollination ecologist, and in his words, “ a scientist who studies how plant’s interactions with their environment (living and non-living) shape their reproduction”. Like I said, my bee guy

If you are one of my “insert natural history category here” people then you get my pictures of said natural history phenomena. Beyond biology, Doug Hartzell, gets my pictures of Nevada’s rocks and mining. He is my geology guy. A catalog of all these specialists-friends who contribute to my rides could be a separate article in itself. Not only do they contribute and participate in my rides but they are always on my mind, in internal conversations as I take in the landscape.

After a long, wet, cold winter we are on the cusp of our wild flower season. My Twitter feed tells me so, even if Northern Nevada just got inches more snowfall overnight. The anticipation is palatable. A superbloom would be pay-off for this winter. Fortunate for us in the Great Basin we have a superbloom that climbs our mountain sides starting at valley floors at below 4000’ and climbs to 10,000’ through the summer. Jake says our floral resources come in pulses, the soil moisture is very ephemeral, so timing among flowers, pollinators and observers is critical. So many of my rides in Northern Nevada have experienced incredible blooms. I have never sought out a bloom as a theme of my rides. They have always been serendipitous.

I went through my photos and curated hundreds of images of flowers and pollinators. Not to worry I will spare you the hundreds and share a few favorites. The take aways and anecdotal trends were:

I need to take more photos of flowers and pollinators, they are crowd pleasers

I typically see blooms starting in April

May and June are peak bloom

July and August are high elevation blooms

Our fall colors are dominated by rabbitbrush

I can only identify a few common flowers, so I really appreciate my friends who put a name to these images. A favorite, Desert Peach

My favorite topic in insect ecology was pollination syndromes. These are a list of flower characteristics that predict the type of pollinator that likely to visit. Color, shape, smell, nectar, patterns, and daily rhythms coordinate a flower’s attractive qualities to a particular type of pollinator. Because we are often talking about co-evolution between a pollinator and plant there is as much specialization of traits within the groups pollinators including size, shape, behavior, and physiology. Broadly speaking we are talking about, bees, butterflies, moths, beetles, flies, bats and others. There is something for everyone in pollination ecology.

Wild pollinators in North America include an estimated 4,000 species of native bees which pollinate about 70% of flowers. Following the math, this leaves thousands of species within the other groups to pollinate the remaining 30%. Occasionally there is a one to one (or few to one) correspondence between flower and pollinator but this is rare or in the case of our incomplete catalog of wild flowers and pollinators, rarely documented. Our incomplete knowledge in the case insect biodiversity cannot be overstated, the most specious groups of animals are beetles (Coleoptera), moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera), and ants, bees, and wasps (Hymenoptera). As a naturalist you are in for a twofer if you observe flowers and pollinators.

As I pedal through the landscape I photograph flowers, pollinators, and flowers with pollinators to share with Jake and others. With location information, what is flying, what is blooming, and when, all becomes important in the canon of pollination ecology. If this is something you are interested in you can take it on as a Citizen Science project with Bumble Bee Watch. Our cell phone cameras do an increasingly better job with macro photography and can record date, time and GPS coordinates automatically. Take a little time to ensure the phone camera’s auto focus catches the pollinator and not the background foliage. The zoom editing features are also improving. Investing time then money in photography is probably good advice. I will be participating in Bumble Bee Watch as currently there are no sightings for the state of Nevada. Our thousand plus bee species deserve better than that.

When is the best time to view flowers and bees in the cold desert? Early spring we see some of the first blooms. As soon as the snow has melted, day time temperatures are reaching the 50’s we see our first flowers. Our lower elevations 3-4,000’ really take off May and June, then quickly as the lower elevations dry out the blooms rush up the mountain sides, making July, August, and September equally rewarding. There is the fall bloom of Rabbitbrush that is also worth checking out if your allergies permit. One of my most memorable rides was in late June through the Desatoya Mountains, between 7 and 8,000’ streams were flowing, the vegetation was lush and the flowers were vibrant. In late July I was treated to flowers and butterflies on Corey Peak above 10,500’. One of the most common groups of flowers I recognize are the lupines. The most memorable was a ride up War Canyon in the Clan Alpine Mountains were I was overwhelmed by thigh-high lupines growing on either side of the road and up the middle. My first thought, I got to tell Jake! Just last year, mid-June I took a group bikepacking over the Calico Mountains. At the lower elevations 4-5,000’ flowers had already bloomed, but above 5,000’ the bloom was impressive. I told the riders Nevada was showing off.

There is so much misunderstanding around bee decline and conservation. In social settings if the topic of “Save the Bees” comes up I bite my tongue and listen. Is there a moment to talk about native bees? Can I say anything constructive to undo the work of popular media? (Nope, that’s why I am writing this) There are numerous threats to apiculture (agricultural beekeeping) diseases, parasites, and pesticide exposure being the top. But there is no risk of European honey bees going extinct. Agricultural costs related to beekeeping will go up. One challenge for North American beekeepers is where to store their bees between agricultural installations. This is a critical time for colonies to recuperate and strengthen. As land use patterns change less area is available and permits are issued to store hives on public lands with little or no regard to native pollinators.

I find beekeeping on the edge of wild spaces or in wild spaces for the sake of conservation, honey production, gardening or apiculture particularly disturbing. I have heard rumor of this happening around the Black Rock Desert by environmentally conscientious people. I get what they think they are trying to achieve, but with due diligence I can’t see how they could come to that conclusion. Honey bees will compete with wild bees for limited resources. They can transmit diseases to wild bees, as well as drive off native pollinators through direct aggression. If there is a break down in the relationship between pollinator and plant we lose both forever. Honey bees can indiscriminately pollinate noxious plants changing plant composition. Honey bees are not a part of regenerative agriculture in places where they are introduced.

Bee and more broadly native pollinator conservation, is about habit conservation. We need to protect our wild spaces from anthropogenic effects of fragmentation, degradation, and climate change to conserve the resources (floral and other elements such as nesting habitat) essential to the pollinators.

I broke down habitat conservation into 3 categories of disruption; fragmentation, degradation, and climate change. These can be applied across all species. Fragmentation refers to large habitats being divided into many small habits. Edges are more vulnerable to disturbance, island populations are vulnerable to extinction, smaller habits contain less biodiversity and less resilience then large contiguous ones. Degradation with respect to pollinators can come from disturbances including pesticide, light pollution, grazing, and introduced species. In extreme combinations degradation results in inhospitable habitat leading to fragmentation. Climate change is impacting native flowers through, drought, fire, sever storms, and changes in temperature. I caught a very timely report on PRX/GBH’s The World, on phenological mismatches, periodical life traits, as a result to climate change. Biological clocks or calendars use environmental cues such as day length and temperature to trigger phases in their lifecycles. These phases may rely on other weather events such as precipitation of interactions with other species. Once pollinators and plants are out of sync there is added stress on the system. Large uninterrupted habitats supporting diverse species will lend to habitat resilience facing climate change.

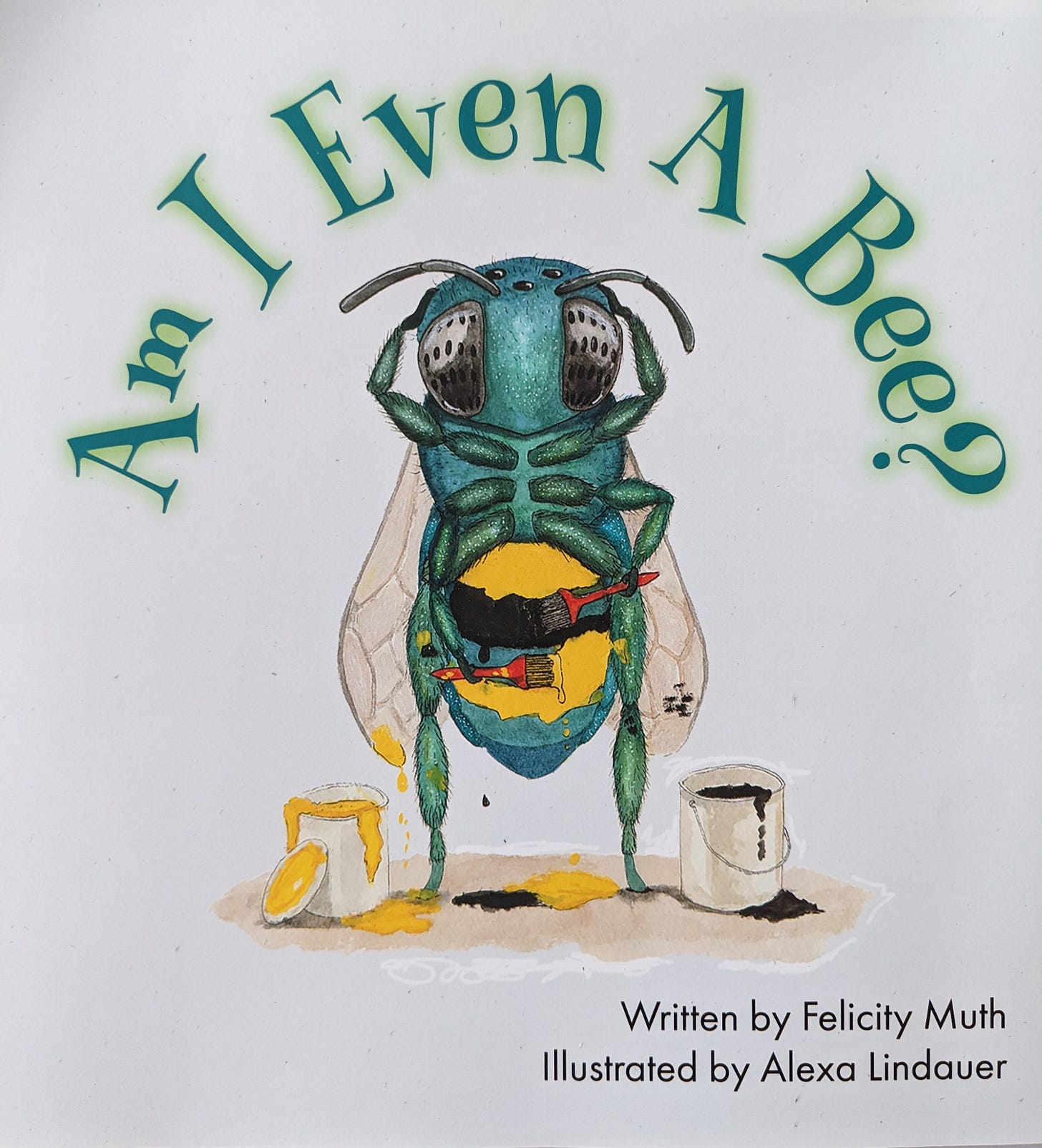

The book, Am I Even a Bee? By Felicity Muth, illustrated by Alexa Lindauer, was one inspiration for this article. Meet Osmia, a blue green solitary Mason bee. Osmia goes through an identity crisis, bees are all around her. Even flies, moths, and beetles look like bees, but she does not. Her friend Xyla, a giant black carpenter bee helped her realize she was a bee, and introduces her to the diversity of bees in the meadow. Osmia is introduced to sweat bees, cuckoo bees, and digger bees.

“At first, they seemed so different.”

Felicity explains the the inspiration to her book in this NPR interview on KUNR, the media’s fixation on the European honeybee, an introduced and feral invasive species, has led people to amateur beekeeping, to save the bees. By writing a children’s book about bee diversity she tackles what is the most important aspect of her research and how to make the biggest impact through her voice as a scientist.

I met Felicity at the community bike shop, the Reno Bike Project. Like many academics Dr. Muth is a bike rider. I learned her lab focuses on bee cognition and my bee guy was in her lab. But it wasn’t a given that Felicity was into bee diversity and conservation. It wasn’t until her book came out, and I heard her interviews on NPR that I understood her interest. Her 2017 interview by our local NPR station is an excellent primer to Felicity’s research, how bee cognition research fits into behavioral science, and how she can explain science to an everyday audience. One thing I admire about Felicity is she has developed her communication skills as a scientist. Check out her Scientific American blog, Not Bad Science (also her screenname on Twitter).

Felicity echoes that reasoning honey bee conservation as a proxy for bee conservation is as reasonable as chicken conservation as a proxy for bird conservation. The media’s focus on diseases, parasites, and pesticide impacts on the honey bees has made it challenging to focus on native bee conservation. If you don’t understand bee conservation is saving 4,000 bee species in North America (1,000 in Nevada, 20,000 world wide) and associated wild flowers through habitat stewardship, then you don’t know.

Now that you know, what can you do? I am not much for telling people what to do. I recommend shaping your opinions with your personal discoveries. This year I plan on taking more photos of flowers. When I do, I will take a look, who’s home is this? Who is doing their grocery shopping here? I expect to see a variety of bees, beetles, butterflies, ants, and flies. My favorite flower loving flies are the bee-mimics, Syrphid flies or H-bees or Hover flies. Common names for insects are just that, common, so you might have your own name for these insects. My favorite flower loving moth is the Sphyngid Hawk moth. This is the “hummingbird” of the insect world, often seen hovering around the garden on warm evenings. Its paired wings beat in a blur giving it its hovering and acrobatic flight. Then from a distance it can extend its proboscis to feed on flowers’ nectar. My favorite butterflies are the Lycinids; Coppers and Blues. I scare them up mid trail and the flutter along with me as I ride. I think of them as living jewels as the sun catches their wings. If I don’t see them resting on plants I find them drinking from damp soils on the edge of streams. One of my greatest experiences was riding along the Black Rock Desert during a Painted Lady butterfly migration. Hundreds to thousands of individuals were making their way north with no consideration to the bike riders they were flying between. With enough observation I should be able to tell who is flying based on the flowers I see and conversely what is blooming based on who I see flying.

Broad scale habitat considerations such as land use that leads to fragmentation and degradation are causes I can get behind. Specifically, overgrazing, large scale solar farms, and mining are rarely considered for their impacts on invertebrates. But vertebrate habitat conservation, such as for sage grouse and desert tortoise, can help protect our native pollinators. I think to myself, what are the impacts on native pollinators and then vote/speak for the bees.

The Nevada Legislature is considering AB221 for the management of terrestrial invertebrates. The letter of support names Monarch butterflies, bumble bees and other non-pest species of greatest conservation need. Currently the Nevada Division of Wildlife does not define invertebrates as wildlife. The idea that habitat conservation for a handful of large vertebrates would also protect invertebrates is common place, but not necessarily true. As an example permitting of bee hives being placed in wild lands between periods of being used in agricultural settings will have little or no impact on deer populations but it will impact native pollinators. Science can guide best practices for land and wildlife managers in these cases.

I hope you can get out and enjoy flowers and pollinators in your gardens and wild spaces. While I intend this newsletter to be more wordy and less photographic I thought the subject matter lent itself to photos.

Select References not linked in text

Do Domestic Honeybees Impact Native Bee Populations?

Focus on Native Bees - great photos!

USGS Bee Inventory Lab on Flickr

March in Review

The winter is holding on in Northern Nevada. Every time I got optimistic and tried to plan a ride the atmospheric rivers dumped a little more snow and rain. After rescheduling a day gravel ride on Winnemucca Ranch Rd only to have it rained out I decided I will postpone until it is good and dry. I was back in Gerlach for meetings related to a Travel Nevada grant. I made an early morning ride on the playa. But my big ride for March was a loop around and through the Monte Cristo Mountains. This mountain had inspired me past trips and I had no idea what sort of route I could put together. Traveling through the unknown scratched that itch. By chance the ride was 52 miles and I had just turned 52 as well.

Ride Calendar April-July

April 1-2 Snowpacking (Slowpacking) overnight in Dog Valley (re-rescheduled, it’s been that kind of winter)

April 15-16 Rides with Friends #1 Around Little High Rock Canyon Wilderness

May 26-28 Black Rock Rendezvous; Rides with Friends #2 Cassidy Mine Loop

June 3-4 Howling, collaboration with WOLF overnight in Dog Valley

June 17-18 Rides with Friends #3 Bikefishing the Granite Range

July 15-16 Rides with Friends #4 Fox Peak Loop

Next month I look forward to sharing my Cabinet Curiosities. Although I do not consider myself a collector, I still seem to pickup things along the way. Thank you for supporting my story telling.

I'm humbled at that. Even though I'm kind of tuned into the looking down, it seems to me, for bikepacking, trying to notice the unusual flora and insect life, as well as the fauna, is a gift to take advantage of when out in the Great Wide Open. Not to mention, there's probably someone somewhere who's observed the benefits of shifting focus from the far and away, to the close and near.

I hope I can join you on one of your trips, I'd really like that.

I need to get my dog bike travel trained first.😄 But that is on a short list of things I want to do this year.👍

I have to say, as a hiker though, I notice small blooming plants even earlier. Granted for cyclists, they are likely overlooked as you roll past…perhaps, if on March and April rides, people wanting to view their surroundings in a new way, schedule a half hour earlier stop when setting up camp and take time to slowly look down and around whenever you pick your camping spot. Give yourself the time to scan low and around, you might catch a small vetch, or buckwheat, or who knows what, if you take a few minutes as you walk around and pay attention to plants that catch your vision as you ramble.

So many can be 3/8” or smaller, it’ll be the unique leaf form, or a brief unusual dot of color that catches one’s eye, and often, they bloom only for a few days, at that.

For Nevadans, it’s a pleasant gamble to start this habit.