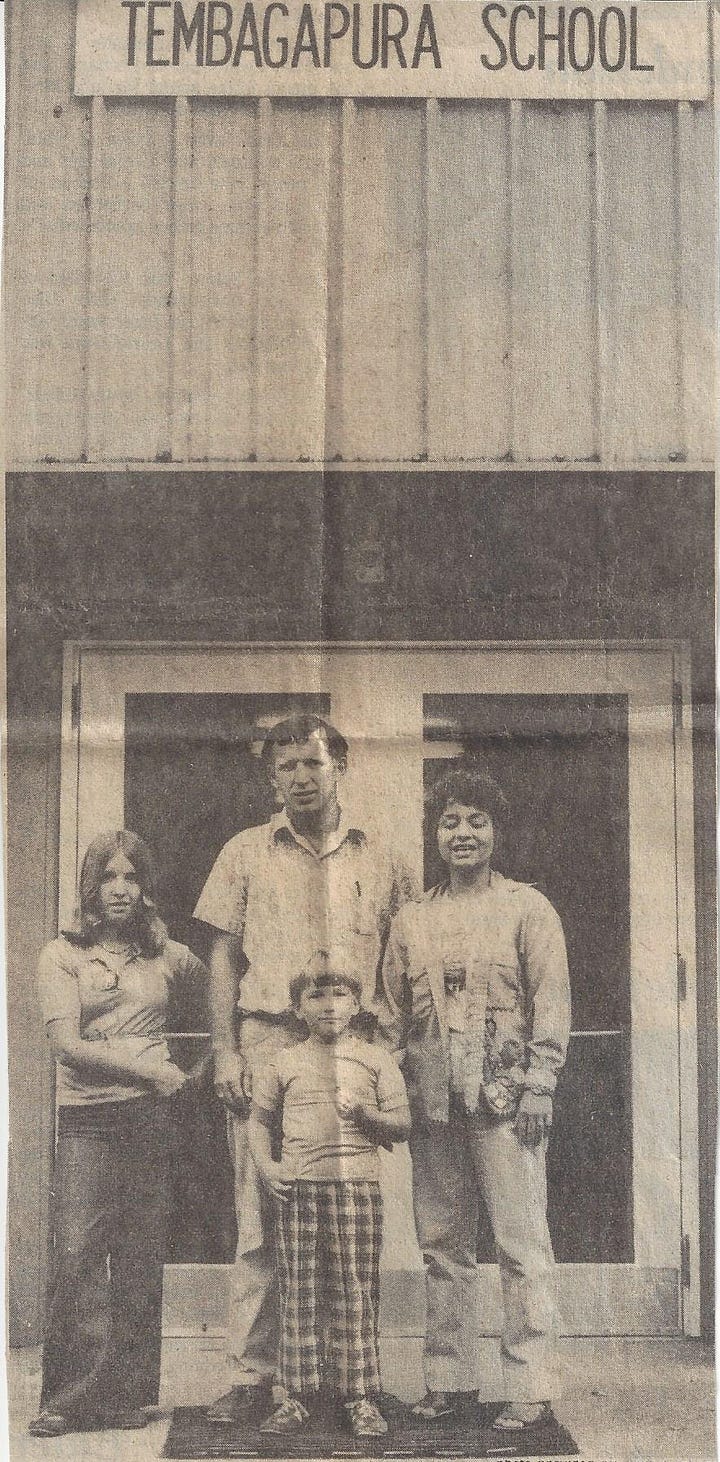

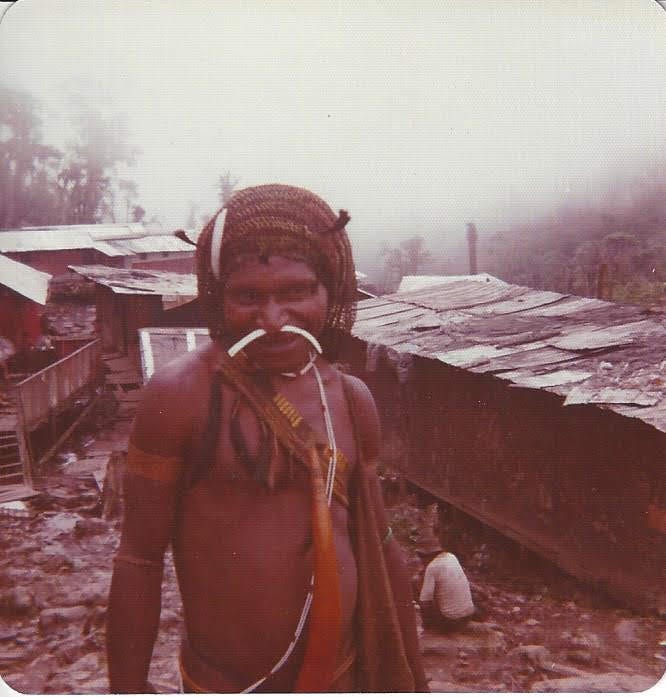

I was born in Eugene, Oregon, so technically I’m an Oregonian and a Pacific Northwesterner. But I grew up overseas, starting at the age of 16 months, in Japan, Indonesia, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Brasil, Romania, and Burma. My parents taught in American-International schools, moving from country to country based on opportunities that were most rewarding to them. In Tembagapura, West Irian Jaya (New Guinea), Indonesia my dad ran a school for the Freeport mining company. Freeport McMoRan has a copper mine in one of the wildest places on earth. One of the most unusual things (and there are many) about this location, it is on the edge of a tropical glacier. The Carstensz glacier is on its way to extinction by 2025.

The Graham Family and neighbor, Tembagapura = Copper Town, West Irian Jaya 1976, I was 5

Living in the Middle East I was unaware of glaciers in Iran and Turkey but I had friends who climbed Mt Kenya and Mt Kilimanjaro. These mountains’ glaciers were the first I remember making news as shrinking. In the late 70’s and early 80’s this news was competing with a hole in the ozone layer, greenhouse gasses, coral bleaching and tropical and temperate deforestation. It wasn’t until high school that I started climbing in the mountains that the cryosphere was on my mind. My ride around Mt. Shasta sealed my resolve to share this with you.

Most glaciers we are familiar with are relatively small fields of ice 0.1 km2 and larger. To visitors they are features of beauty to observe and photograph or physical challenges to climb that fuel local tourist economies. Scientists study glaciers as a snapshot of climatic/atmospheric past. Dissolved gasses trapped in ice can give record to the conditions as far back as the Pleistocene. While glaciers may be millions of years old, the oldest ice from glaciers around the world ranges from less than 100 years old to 1,000,000 years old. Glaciers well known for their downstream effects. Under healthy conditions glaciers act as cold water reservoirs for streams and rivers critical for sustaining a way of life for billions of people world wide. Locally, rivers that rely on glacial meltwater for cold water habitat are warming to a point that cannot sustain cold water species of invertebrates or fish. In the case of the Nooksack River with headwaters in the glaciated peaks of Mt Shuksan and Mt Baker, this fragile ecosystem that supports 8 species of salmon and trout as well as the traditional ways of life for the Nooksack and Lummi Tribes relies on being shielded from temperature swings by cold glacial melt. Glaciers in rapid retreat alter the normal river flows which in some cases are incompatible with local and traditional agricultural practices. Once a glacier is gone the watershed will be at the whim of groundwater, precipitation and snowmelt. In the case of agricultural lands at the base of Mt. Kenya, the effects of climate change that are erasing its glaciers are also increasing temperatures, droughts, and floods. As a result the impacts of food insecurities are leading to community violence as ranchers move their livestock to find water and feed. Glaciers are a source of community/national pride, Nevada has one, Wheeler Peak Glacier, Japan just discovered their first (of now seven) in 2012, and school children in Jakarta learn about their “Eternity Glacier” expected to disappear by 2025.

Very briefly, what is the life a glacier? It begins when perennial snowfield compresses and freezes into an icefield. Once the icefield reaches a critical mass it will begin to move, this is a glacier. Glaciers can connect mountains to the sea, creep down a valley, spread over a flat surface, and hang off the continent floating in the ocean as an ice shelf. The most fascinating glacier type I found was when I was looking for examples of glaciers in Romania, the Scărișoara cave glacier. Even protected underground it too is in the news for shrinking due to climate change. Glaciers have a seasonal heart beat or breath, snow accumulates in a snowfield above the glacier, forms a dense layer called firn that later compresses into ice, this is the accumulation zone - the inhale. As the glacier moves and spreads it melts, sublimates, or calves icebergs into the sea from the bottom, the ablation zone - the exhale. These basics remind me middle school earth science was a long time ago.

The equation of inputs to outputs is not in the favor of sustainable glaciers. It begs the argument, are glaciers disappearing from the heat, in the ablation zone of the glacier? Or are they disappearing as a result of drought, a lack of inputs in the accumulation zone? While I understand the argument and the models needed to tease these two factors apart, my simple explanation is that it needs to be both rising temperatures and decreasing precipitation that kills the balance sheet for glaciers. In the case for Mt. Baker’s Sholes glacier, it would require 900” of snow fall to offset the melting it experienced in 2021. That is 50% more than average, not an impossible amount, just unlikely. How many years of “unlikely” will the glacier sustain? In the case of Mt. Kenya’s Lewis glacier researchers argue it is disappearing from a lack of precipitation and protective cloud cover that accompanies it. Whether it’s the heat or humidity, glaciers need to catch their breath.

The forecast for glaciers is grim. Looking to 2100, two thirds of glaciers are expected to disappear. This comes with a range of less than half to 83%. Long range and world wide glacial mass losses are very difficult to comprehend. But looking to near examples of glaciers, such as on Mt Shasta and further north into the Cascade Range makes it all more real. Yet even in recent history there have been periods of growth. For the Pacific Northwest scientists do not discount that warming of the ocean (El Nino) could result in increased precipitation in the Cascades. Projections over the next 10-30 years indicate significant losses with the potential for Glacier National Park, MT to be glacier free.

I am not a fan of the “canary in the coal mine” analogy for glaciers acting as predictors of global warming. I don’t like the idea of glaciers being sacrificial, but it is commonly quoted within the climatology field. I do think glacial disappearance at an accelerated pace as a global phenomena is glaring evidence of global warming/climate change. Glaciers can be easy to identify, are sensitive to climate change, and valued by society. For those reasons it is to make them a poster child for conservation. At the same time there is nothing easy about understanding glaciers, their relationship to climate change and our relationship to them. I see glaciers as massive ancient and mysterious things. They are a thing of beauty. As an angler I appreciate their ability to buffer temperature swings in cold water streams. In my mind I was never meant to see a glacier disappear within my lifetime. On the surface I realize this is an unrealistic expectation. The Lathorp Glacier on southern Oregon’s His-chok-wol-as (Klamath name), Mt Thielsen vanished just in the last years. That seems reasonable as an isolated case, it was a tiny glacier in a warm climate. But I cannot accept it as a global phenomena. In my mind the loss of a glacier is an extinction. But scientists suggest that glaciers can come back given the right conditions. A cooler climate with fewer greenhouse gasses and increased precipitation are the recommended conditions. I hope I can witness the birth of a glacier.

If you have interests in glaciers and the landscapes they create I recommend going and taking a look. That is what I did in my ride around Shasta. I crossed a few washed out roads that I later learned were caused by the rapid glacial melt. I had assumed they were washed out by heavy thunderstorms. By riding around the mountain I had a 360o perspective of the lack of snowpack. My plan is to return, bike to the edge of the wilderness and hike to one of the glaciers for a closer look. I will have my fly rod on the next trip to see if I can trick the local trout with a dry fly. I invite you to come with and see for yourself!

Meltwater from Konwakiton Glacier made for a cold crossing at Mud Creek, Mt Shasta

I hope this doesn’t read like a fever dream. I have dozens of tabs open on my computer in trying to pull together the information for this essay. I will share the select here. My favorite part in this process was learning a little about glaciers in the countries I grew up in. In Burma my family lived in Rangoon on the Irrawaddy River. While the Irrawaddy is primarily influenced by monsoonal rains its headwaters are within 129 glaciers in the eastern Himalayas. This concept had never crossed my mind in the seven years my family lived in Burma. Learning about Romania’s subterranean glacier was also a gem. While we are destined to lose glaciers with predictable as well as unforeseen consequences scientists remind us that communities are resilient and will find solutions to life without glaciers. If you are interested check out some of the links I shared.

What is a glacier?

Glaciers growing up

Burma (long video on Himalayan glaciers), Irrawaddy Headwaters

Pacific Northwest

Mt Shasta, and from Mt Shasta News

The History of Ice: How Glaciers Became an Endangered Species

February in Review

It’s been a tough winter for planning group rides but I spent some time scouting. I did find some dry roads on my visit to Gerlach over the 8th and 9th. I was in town for a meeting about a proposed multi-use interpretive trail along the south edge of the playa. It is an exciting project that I will keep you updated on. The second meeting was a Citizen’s Advisory Board meeting with regards to the prospects of ORMAT building a geothermal power plant on the edge of Gerlach. While the community of Gerlach voiced their support for renewable energy they are opposed to the eye-sore and ear-sore consequences of having a power plant on the edge of their town. In addition to the industrial infrastructure the burden the power plant could place on the aquifer could have devastating effects on area springs as well as creating the potential for sink holes below the town. I will keep you posted on this as well as other mining proposals in Black Rock Country.

Locally, I was able to ride on packed snow on Henness Pass Road, Dog Valley area, as well as Hunter Lake Rd, Peavine Rd, and the Steamboat Ditch Trail. There was a dry window mid-month and I got on dirt above Golden Valley. These are favorites, but I am itching to ride something new!

Ride Calendar March-June

March 11-12 Slowpacking (Fat bike) Overnight in Dog Valley

April 15-16 Rides with Friends #1 Around Little High Rock Canyon Wilderness

May 26-28 Black Rock Rendezvous; Rides with Friends #2 Cassidy Mine Loop

June 3-4 Howling, collaboration with WOLF overnight in Dog Valley

June 17-18 Bikefishing the Granite Range

Next month I am excited share the importance of native pollinators and reviewing the book, Am I Even a Bee by local author Felicity Muth. Thank you for your support of my story telling!

What an awesome read, & good to put a spotlight on things most of us just overlook with the arrogance of the human race!

Hopefully we ALL can start to see new glaciers form.

This is a great essay. I feel much more connected to glaciers now. They are awesome beings with many stories to tell. I appreciate all the reseach, and presenting it in words I could understand and connect with mentally and spiritually. Thanks for sharing snippets of your life. I am glad you revisited the glaciers of your younger years. I have many pictures of the sprawling, circuitous Irawaddy. And to think it's headwaters are from glaciers in the Himalayas! Wow...not that would be a trip to see. Keep writing, keep sharing. Look forward to reading about pollinators.